(I was originally intending just one more post on this, but now I think it will work better as two separate posts.)The following is an actual ad placed in an Irish newspaper some years ago: “1985 Blue Volkswagen Golf. Only 15 km; only 1 driver. Only first gear and reverse used. Never driven hard. Original tires; original brakes. Original fuel and oil. Owner wishing to sell due to employment lay-off.” Sound a little odd? Take a look at the picture.

The conventional wisdom is, you need a car . . . Sometimes, though, following the conventional wisdom is a pretty foolish thing to do. Conversely, sometimes those the conventional wisdom calls foolish aren’t fools at all. Sometimes they’re actually three steps ahead of the rest of us. Take the example of Fred Smith, the founder of Federal Express and the man who created the overnight delivery which we now take for granted. He first proposed this in a paper when he was a student at Yale University; the professor gave him a C, telling Smith that his idea was interesting but couldn’t be done. Smith went ahead and did it anyway, even though a Ph.D. had told him he was foolish. We know who was right.The thing is, the world just isn’t as wise as it thinks it is, and so sometimes you have to be willing to be a fool in order to get anywhere. Which might sound like a truism, but it’s an important thing to remember. Even in the church, too often we get caught up in the conventional wisdom about life, and when that happens we start to judge the gospel by the standards of the world’s wisdom, or to try to make it fit with what we consider wise. The problem with that is that it’s a demand that God play by our rules, and he’s just not going to honor that; he’s not going to conform the truth to our idea of wisdom. The gospel is not wisdom by any human standard—it is a contradiction to human wisdom.God’s foolishness begins with a crucified Messiah. Many of us have gotten used to this, as Easter goes by every year, but if you really stop to think about it, it’s crazy. As the great New Testament scholar Gordon Fee put it, “No mere human, in his or her right mind or otherwise, would ever have dreamed up God’s scheme for redemption—through a crucified Messiah. It is too preposterous, too humiliating, for a God.” Put another way, no self-respecting God would put himself through something like that—becoming human, sharing all the unpleasant and messy parts of life, and then submitting to be tortured to death—and for what? For us? Surely that’s beneath God’s dignity, isn’t it? Yes, it is; no self-respecting God would do a thing like that—which tells us something very important about God: he will never let his dignity get in the way of his love for us.If the whole idea of a crucified Messiah is God’s foolishness, then surely Jesus was God’s designated fool; and for all that we tend to think of him as a great wise man and a great teacher, he made a lot of those around him think he was a fool, or worse. It wasn’t long into his ministry before Jesus had convinced his family that he was insane, and the priests that he was possessed by Satan himself. After all, he just didn’t act like a normal person, and his teaching challenged almost everything the religious leaders taught, in one way or another. He upset people’s expectations, and sometimes their furniture; and when he started to explain things to his disciples, it only upset them, too.Jesus just wasn’t what anyone was looking for. The Jews knew what Messiah would look like; he would come with signs of God’s power and lead his people out of their captivity, just as Moses had done so long before. The Greeks, on the other hand, being the philosophical types, had their systems and divided the world into all its appropriate boxes; they were looking for a perfectly reasonable God who fit their system, who fit into their boxes. Both were sure they had God all figured out; to both, the idea of a crucified God was scandalous—indeed, it was insane.And yet, it was through this crazy plan—and this equally crazy Messiah—that God saved the world. It wasn’t through any of our own work or our own wisdom that God saved us, not even the best we could offer; in his own wisdom, God saw to that. Though this all looks foolish to the unaided eye, God’s foolishness outsmarts our wisdom. Christ’s crucifixion, the ultimate act of powerlessness, is the ultimate act of God’s power; his crucifixion, which is complete foolishness to those who are lost, is the ultimate act of his wisdom. We don’t have the choice to look for some wiser way, because there isn’t one; we can only trust God and be saved by his wise foolishness, or cling to our own wisdom and be lost.

Category Archives: Religion and theology

God’s Own Fool

OK, so this one is Erin’s fault; I got along exploring her blog after her response (which I very much appreciated) to the meme I started, and ran across her post on foolishness and God. Apparently it’s part of a synchroblog that she and some other folks have going; but while I might not resonate with this in the same way as they do, this is something with which I resonate powerfully nonetheless. It begins with Jesus, God’s designated Fool; and it ends with us, his designated fools. I’ll talk about that tomorrow. For now, I want to let Michael Card do the talking, because I’ve always loved this song.

God’s Own Fool

It seems I’ve imagined Him all of my life

As the wisest of all of mankind;

But if God’s holy wisdom is foolish to men,

He must have seemed out of His mind.

For even His family said He was mad,

And the priests said, “A demon’s to blame”;

But God in the form of this angry young man

Could not have seemed perfectly sane.When we in our foolishness thought we were wise,

He played the fool and He opened our eyes;

When we in our weakness believed we were strong,

He became helpless to show we were wrong.

And so we follow God’s own fool,

For only the foolish can tell;

Believe the unbelievable—

Come, be a fool as well.So come lose your life for a carpenter’s son,

For a madman who died for a dream,

And you’ll have the faith His first followers had,

And you’ll feel the weight of the beam.

So surrender the hunger to say you must know,

Have the courage to say, “I believe,”

For the power of paradox opens your eyes

And blinds those who say they can see.ChorusWords and music: Michael Card

© 1985 Mole End Music

From the album Scandalon, by Michael Card

More tomorrow.

Gospel witness

Barry’s post today on evangelism got me thinking. Evangelism has gotten a bad rap with a lot of people thanks to the high-pressure approach of a few—the sort of folks who grab random strangers, stick a half-dozen Scripture verses in their ear, badger them into saying a certain prayer, stuff a tract in their pocket, and walk off confident they’ve “saved another soul.” I’m sure God can use that; after all, God used Jacob, he used Jonah, he used Peter—who am I to say God can’t use anybody or anything. But what we tend to forget is that in Acts 1, Jesus didn’t say, “You will do witnessing,” he said, “You will be my witnesses.” Our call as Christians isn’t to “save souls” in that sense, but to share the life Jesus has given us with the people around us; and we aren’t called to witness to Jesus just by memorizing some spiel, we’re called to be his witnesses by the way we live our lives. As St. Francis of Assisi put it, “Preach the gospel at all times. When necessary, use words.”

Now, the downside at this point is that we often don’t hear this correctly; we have the tendency to mentally translate this into “I don’t have to tell people about Jesus, I just have to go out and live my life and that’s good enough.” Well, yes and no, sort of. Go back to that quote from St. Francis and think about this for a minute: “Preach the gospel at all times.” That’s the standard: our lives are to be sermons on the word of God, backed up by our words. Our call as disciples of Christ is to go out into the world and live in it as he did—talking with others about our Father in heaven, and just as importantly, showing his love to those around us in every way we can think of. We are called to do the work he did: to feed the hungry; to care for the sick; to welcome the outsider; to defend the oppressed; to lift up the downtrodden; to love the unlovable; to break down the barriers between race and class and gender; and to speak the truth so clearly and unflinchingly, when the opportunity arises, that people want to kill us for it.

Spiritual discipline?

So my friend Wayne credits me, among others, with “helping me to view blogging as in many ways a spiritual discipline for the 21st century”; and that started me thinking, because it had never occurred to me to consider it that way. Dallas Willard, in his classic book The Spirit of the Disciplines, has this to say about them:

We can, through faith and grace, become like Christ by practicing the types of activities he engaged in, by arranging our whole lives around the activities he himself practiced in order to remain constantly at home in the fellowship of his Father. . . . When we call men and women to life in Christ Jesus, we are offering them the greatest opportunity of their lives—the opportunity of a vivid companionship with him, in which they will learn to be like him and live as he lived. This is that “transforming fellowship” explained by Leslie Weatherhead. We meet and dwell with Jesus and his Father in the disciplines for the spiritual life.

We could also say that spiritual disciplines are practices in which we engage in order “to cultivate our daily lives into fertile ground in which God can bring growth and change”; practicing the disciplines forms and shapes our lives much as the farmer forms and shapes the soil, clearing away unhelpful growth and carving the ground into furrows that will receive the seed and the rain, so that the crop will grow.

Now, I could go on and talk about the role and importance of spiritual disciplines such as silence and solitude, prayer and fasting in actually living the life to which Christ calls us; but what I’m wondering is, does blogging really belong on that list? Not that blogging is automatically a spiritual discipline—but then, none of the disciplines are automatic. You have to be, well, disciplined about them. The question is, granted that we can blog unspiritually just as we can pray unspiritually, can we really use blogging as a discipline for spiritual growth?

It’s a question I’d never thought about before; but I think we can. What’s more, I think this is something those of us who are Christians who blog need to consider seriously and carefully. That being so, though I haven’t been a meme-y sort, I’d like to pose it to you as a meme:

In what ways can you use blogging as a spiritual discipline?

For myself, the first thing I’d have to confess is that I often don’t. Granted, I never have on a conscious level; but the thing about spiritual disciplines, properly understood, is that they aren’t just something we do, they’re something to which we submit. If, for instance, your prayers are merely a litany of your own arguments and opinions and requests, with no room in them for anyone but yourself, that’s not a spiritual discipline, because there’s no space in there for you to be changed. Similarly, if all I do in blogging is assert my own ideas and contentions, whatever the value of those ideas might be, it’s not a spiritual discipline; someone else might be formed by that, but I certainly won’t be. It seems, then, that in using blogging as a spiritual discipline, a key element has to be receptivity.

Given that, then, and given the natural tendency of human beings to want to challenge others without challenging ourselves, my first thought is this: blogging can help me see the gaps between what I live and what I believe. Put another way, one spiritual discipline for me in blogging is to apply my beliefs and their implications not only to the lives of others out there in the culture, but also to myself and my own life. If I say x, and that means someone else ought to change and to live differently, how does it mean that I need to change and live differently? It’s an important question, and one that blogging as a discipline can force me to face.

That’s one thought, and certainly not the only one; I’d like to hear what others have to say. If you happen to come across this post, I’d like to challenge you to think about this question, and answer it for yourself. To start the ball rolling, I’m specifically tagging Wayne (of course), Hap (ditto), and Dave Moody at blog 137. You three, and whoever will, I ask to do the following:

1. Answer the question on your own blog. (If you don’t have one and would like to chew on this anyway, please do so in the comments on this post.)

2. Keep this going–tag a friend or three.

3. Come back and post a comment here to let me know you’ve responded, and where to find your response. I would very much like to see what others have to say on this.

Thanks.

The Great Counter-Attack

Even people who couldn’t tell George Santayana from Carlos Santana are familiar with some form of his dictum that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. Like most famous comments, it’s been overplayed, and many people tend to quote it glibly, without thinking about it; but it’s still an important warning of the consequences of failing to understand our history. To this, we might add that those who don’t remember the past will have no sense of perspective about the present.

I was reminded of that truth recently in reading the novelist Sandra Dallas’ review of the book Verne Sankey: America’s First Public Enemy, by South Dakota circuit judge Timothy Bjorkman. As the title indicates, Sankey was the first person ever to be named Public Enemy #1 by the FBI, “because he was the first to realize that in the wake of the Lindbergh baby abduction, kidnapping could be a lucrative gig”; he’s little remembered today because he wasn’t flashy, while so many of his criminal contemporaries were. As Ms. Dallas writes, “This was the Great Depression, when the rich were held in low esteem and the robbers and others who preyed on them were rock stars, glorified by the press. It was the era of Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, John Dillinger and Machine-Gun Kelly.” That set me thinking, because there’s much complaint in certain quarters about the glorification of street thugs by segments of American culture—which I certainly agree is a bad thing; but it’s often joined to the assumption that America is in decline from some past golden age when these things didn’t happen, and that just isn’t true. One might, I suppose, argue that the thugs some people glorify these days lack the style of past generations of celebrity criminals; but if we’re honest, we have to admit they’re really very little different.

The reason Santayana’s comment is largely correct is that if we don’t understand our past, we really can’t understand our present, either—which leaves us vulnerable to those who would use a skewed picture of the past against us. Granted, a truly unbiased understanding of history is probably beyond our grasp, but we need to get as close as we can in order to defend ourselves against those who interpret it to serve their own agendas (whatever those might be).

Perhaps the most significant example of this nowadays is in regard to Islam, where the Crusades are often presented as a great crime by Christendom against an unoffending Moslem world, launched for no apparent reason. The truth of the matter is far different. As Hugh Kennedy shows in his book The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In, the early 7th century AD saw a new propulsive force break into world history: the conquering armies of Islam. Within the first hundred years, they had spread across most of the Christian world, and as Dr. Philip Jenkins notes in his excellent review in Christianity Today, “Before the Crusades”, this “tore Christianity from its roots, cultural, geographical, and linguistic.” The Islamic conquests essentially created the Western Christianity we now know, as the church was forcibly disconnected from its Asian heritage and character; and the Muslim armies didn’t stop there, occupying most of Spain, invading Italy and the Balkans, and even reaching as far as the gates of Vienna.

However wrong the Crusades went over time (such as the Fourth Crusade, which conquered and sacked not Muslim Jerusalem but Orthodox Constantinople, in whose defense the First Crusade had been launched), they began as a defensive action, a grand counter-attack intended to roll back the Muslim armies before they conquered all of Europe. In the end, they didn’t succeed; it would not be until the breaking of Ottoman power at the Battle of Vienna in 1683 that the tide of Islamic conquest would finally turn for good. Still, though we must never gloss over all the wrongs committed by Crusaders, it’s important to understand that the Crusades as such were an eminently justifiable military and cultural response to Islamic military aggression; they were a counter-attack launched in a great war begun by the other side.

The Christian discipline of forgiveness

I’ve been thinking, periodically, about the whole question of repentance and forgiveness ever since Hap’s post a couple months ago on the Emerging Women blog; and so I was interested, in dropping in on Dr. Stackhouse’s blog this morning, to see that he began his reflections on Advent this year with that very theme. It’s supposed to be the first post in a two-part series; the second part isn’t up yet, but there’s more than enough to think about already. I particularly appreciated this section:

Repenting and forgiving are not pretending the past didn’t happen and that what seemed evil is somehow okay. Repentance and forgiveness name what was wrong as wrong. If it weren’t wrong, it wouldn’t need repenting of and forgiving! Repentance and forgiveness also do not pretend the future will be sunny and that there will be no repetition of wrong. You may have noticed that people generally don’t become perfect after a single round of repentance and forgiveness. Jesus tells us to forgive the same person seven times in a single day to make hyperbolically clear that a single episode of repentance and forgiveness may not be the end of it.

and this one:

To forgive the offender is to give a great gift. It cuts the offender free from the Jacob Marley-like shackles of past sins. It gives the offender a fresh start. It does not “re-member” the past sins by repeatedly bringing them up again and fastening them afresh to the present person. It leaves the past in the past, and lets people go ahead into the future. But “forgive and forget” is bad advice, and on two counts. First, one can’t do it. Second, one shouldn’t. Refusing to pretend as if the past didn’t happen instead helps us act realistically to maximize shalom for everyone involved.

I like that—remembering as “re-membering,” taking the the wrongs others have done us in the past and giving them new bodies (as it were) in the present, giving them new life to cause hurt all over again. Thus Dr. Stackhouse concludes,

So let us repent and let us forgive, and neither forget nor re-member. In that paradox is the path of a hopeful, healthful future.

That’s the idea in a nutshell, except that I don’t think it’s a paradox, really, just a middle way: the way of acknowledging the past but not living there, letting it be the past and not the present.

Harold O. J. Brown, RIP

Harold O. J. Brown wasn’t one of this country’s most famous evangelicals, and I don’t recall Time putting him on its list of the 25 most influential; but he may well have been one of its most important. A multivalent scholar, writer and teacher, he had a remarkable career, but it’s instructive that those who knew him were less impressed by what he had accomplished than by who he was in Christ. In particular, it’s worth noting that he never had the high public profile of a Jerry Falwell or a Ted Haggard, not because he lacked the gifts—he was a prodigiously gifted man—but because he never wanted it.

Of the various eulogies for the Rev. Dr. Brown, the one I’ve appreciated the most has been this one, from S. M. Hutchens in the latest Touchstone. Since it isn’t available on their website, I reproduce it (by permission) here in its entirety.

At a gathering of Harold O. J. Brown’s friends after the memorial service in his honor, William D. Delahoyde, a Raleigh attorney and protégé from his Deerfield days, rose to state what I am sure was a consensus: While it was doubtful his passing would be noted by the general media, most of us there thought that in knowing him we had a brush with greatness.In that company the observation bore a peculiar taste and weight, for the people with whom I had been conversing at the obsequies, especially the older ones who had known him for many years, were not the sort for whom the attribution would pass easily.Many of them were, after all, members of America’s nobility, old Harvard grads who knew, and often were on familiar terms with, people whom most of us have only read about. Listening to them reminisce was like an evening spent in a well-marked part of my library—but here the books were alive.All of us knew Joe as a brilliant intellect: the valedictorian of a Jesuit high school who took his degree in Germanic Languages and Literature from Harvard College magna cum laude, who absent-mindedly forgot that he had been accepted at the Medical School, instead studying theology on the continent on Fulbright and Danforth fellowships, returning to Harvard after and Evangelical conversion in Germany to take his doctorate in Reformation history under George Hunston Williams. He lectured or conversed in German, French, Polish, Swedish, Russian, Hindi, and several other languages.Like Max Weber, who taught himself Russian to pass the time during a week of convalescence, Joe’s talent for language and the breadth of his literary knowledge were legendary among those who knew him. Conspicuous at the gathering were any members of his Harvard rowing crews, whom he had coached to notable victories, including first-place cups at the Henley Royal Regatta.Most of us there had met him later than the Harvard days, and heard of all this as the prelude to a distinguishe pastoral, teaching, and journalistic career with InterVarsity in Europe, Park Street Church in Boston, Yeotmal Seminary in India, Christianity Today, Trinity-Deerfield, the Religion and Society Report, and finally Reformed Theological Seminary in Charlotte.A strong Protestant, Joe was a friend of Christians wherever he found them, including us at Touchstone. He wrote several pieces for the magazine, and served as one of the principal speakers at the Rose Hill conference in 1995.He was a particularly bold (sometimes to the point of folly) mountain climber, ran—or if he had to, walked—marathons, despite being plagued with the congenital lower-spine deformity that caused his distinctive posture and gait. He was a loving and attentive husband to Grace—a redoubtable counterpart, fully as remarkable in her way as he was in his—and father to Cynthia and Peter. While perhaps most widely known for his political and intellectual leadership in the pro-life movement, he was in scores of individual lives a paraclete who by dint of his gentle attention and concern became Kierkegaard’s pinch of spice that made all the difference.But this suffices to represent his phenomenal accomplishment. Joe was embarrassed by such notice, and on his deathbed, Bill Delahoyde told us, he emphatically said—or rather wrote, for he could no longer speak—that he did not see in himself the man that others saw in him. His childhood and early family life, of which he spoke little, was odd and less than satisfactory, and what he became cannot be explained except through the glass of redemption. Here, to be sure, was great native ability and desire to achieve, energized by a strong sense of noblesse oblige, and a desire to love so that he might be loved in return.This may become the stuff of greatness, but on reflection I think this is perhaps not really what we are speaking of here. The proper word is “glory,” in which Joe’s observation about what he could not see in himself merges into what he did see in Another, and which we beheld in him.This glory was manifest in a humility that dispersed its gifts—which in others would have gone into the construction of a world-historical character—among his friends as the animating force behind a task to complete. His kenosis was not carried out simply in consent to a divine mission to the world, but in befriending us—making himself of minor repute principally by concentration on the cultivation of others. Thus we beheld his glory, but in its very revelation it was hidden, and so it is with the best of his servants, who, taught in his school and following his example, tend to spend their lives giving away what “great” men have so often learned to keep for themselves.Harold O. J. Brown, whose view of his work at the end of his life echoed that of Thomas Aquinas, saw no greatness in himself because he had lived long in the shadow of his Master, simply doing for others what had been done for him. But he will be happy, I think, when his friends rise up to say that they saw in this the reflected glory of the Lord.

Christian escapism

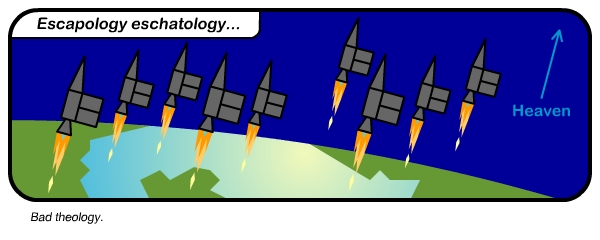

I have Hap to thank for pointing me to ASBO Jesus, Jon Birch’s strange, often fascinating, and frequently very funny comic blog. (I have Birch to thank for the following explanation: “btw. for the non british among you… an ‘asbo’ is an ‘anti-social behaviour order’… the courts here award them to people who are deemed to be constant trouble in their neighbourhoods… presumably according to their neighbours!”) I’ve appreciated any number of his comics, but I especially like this one, because I too have a problem with the whole idea of the “Rapture.” I agree with Birch that it’s bad theology, though we can argue that at another time; more than that, it’s bad exegesis.

I have Hap to thank for pointing me to ASBO Jesus, Jon Birch’s strange, often fascinating, and frequently very funny comic blog. (I have Birch to thank for the following explanation: “btw. for the non british among you… an ‘asbo’ is an ‘anti-social behaviour order’… the courts here award them to people who are deemed to be constant trouble in their neighbourhoods… presumably according to their neighbours!”) I’ve appreciated any number of his comics, but I especially like this one, because I too have a problem with the whole idea of the “Rapture.” I agree with Birch that it’s bad theology, though we can argue that at another time; more than that, it’s bad exegesis.

I imagine that statement will surprise some people, who are no doubt already flipping to 1 Thessalonians 4 to prove me wrong. I can hear them now: “See, it says, ‘The Lord himself will descend from heaven with a cry of command, with the voice of an archangel, and with the sound of the trumpet of God. And the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who are left, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air, and so we will always be with the Lord.’ See, there’s the Rapture right there!” Fine, except . . . it isn’t. Does that text say the Lord will return? Yes. Does it say we’ll all meet him in the air? Yes. But look closely and notice what it doesn’t say: which direction we’ll go from there. The assumption behind the idea of the Rapture is that Jesus will go back to heaven for a while and we’ll go with him—but the Scripture doesn’t actually say that. It’s only an assumption.

Now, I can predict the most likely rejoinder here: “It’s obvious!” Except, once you get outside the assumptions of our culture, it isn’t. To understand what’s really going on in 1 Thessalonians, remember the parallels between this passage and the wedding parables of Jesus. In several places, Jesus compares those waiting for his return to people waiting for the bridegroom. Thus for instance we have the parable of the wise and foolish bridesmaids, in Matthew 25. In that parable, the crisis comes for the foolish bridesmaids when the cry comes, “Here comes the bridegroom! Come out to meet him!” Here’s the parallel to 1 Thessalonians 4: the Lord, the Bridegroom, returns, and we go out to meet him and escort him to the house.

In other words, the coming of Christ Paul talks about isn’t a halfway coming to pick us up and leave the rest of the world to rot; it’s his final return to earth, and we will go out as the wedding party to escort him in. There’s no Rapture in this passage, no “Get Out of Trouble Free” card; only our wishful thinking makes it so.

Thank God for God (a Thanksgiving meditation)

“Naked I came from my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return there;

the LORD gave, and the LORD has taken away; blessed be the name of the LORD.” —Job 1:21

During the time of Napoleon’s reign in France, there was a political prisoner by the name of Charnet. That is to say, there was a man named Charnet who had unintentionally offended the emperor by some remark or another and been thrown in prison to rot. As time passed, Charnet became bitter and lost faith in God, finally scratching on the wall of his cell, “All things come by chance.”

But there was a little space for sunlight to enter his cell, and for a little while each day a sunbeam cast a small pool of light on the floor; and one morning, to his amazement, in that small patch of ground he saw a tiny green blade poking out of the packed dirt floor, fighting its way into that precious sunlight. Suddenly, he had a companion, even if only a plant, and his heart lifted; he shared his tiny water ration with the little plant and did everything he could to encourage it to grow. Under his devoted care, it did grow, until one day it put out a beautiful little purple-and-white flower. Once again, Charnet found himself thinking about God, but thinking very different thoughts; he scratched out his previous words and wrote instead, “He who made all things is God.”

The guards saw what was happening; they talked about it amongst themselves, they told their wives, and the story spread, until finally somehow it came to the ears of the Empress Josephine. The story moved her, and she became so convinced that no man who loved a flower in this way could be dangerous that she appealed to Napoleon, and persuaded her husband to relent and set Charnet free. When he left his cell, he took the little flower with him in a little flowerpot, and on the pot he wrote Matthew 6:30: “If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, how much more will he clothe you, O you of little faith?”

There’s a lesson in Charnet’s story—the lesson of Job, I think. I struggled for years to make sense of that verse, until I found the key in an observation made by Rev. Wayne Brouwer, a Christian Reformed pastor in Holland, Michigan. Rev. Brouwer, writing on Psalm 22, muses, “Maybe it’s not that believers are grateful to God but that those who are grateful to God are the ones who truly believe him. Only those of us who are truly thankful are able to ride out the storms of life which might otherwise destroy us. Only those who have an attitude of gratitude know what it means to believe.” In other words, the root of our faith is gratitude.

We talk about the patience of Job, but in reality Job showed very little patience; what he did show was great faith, and that faith was firmly rooted in his determination to remain grateful for all the Lord had given him despite his losses. Thus he can say here, “The Lord gave, the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord”; thus he can affirm at another point, “I know that my Redeemer lives, and that at the last he will stand upon the earth . . . in my flesh I shall see God.” In the same way, once Charnet found something for which to be thankful, that little plant struggling through the hard, dry earth, he found Someone to thank, and his faith grew back along with that little plant. Before that point, faith was impossible for him, because there was no root to sustain it.

If our gratitude depends on the number of our gifts exceeding a certain critical mass, if we miss the Giver for the gifts, then we have a shallow faith indeed. The example of Job calls us to a deeper gratitude, and a deeper faith, a faith that is able to see God and give thanks even when things aren’t going well. This is the faith the poet Joyce Kilmer expressed when he wrote, “Thank God for the bitter and ceaseless strife . . ./Thank God for the stress and the pain of life./And, oh, thank God for God.” That’s really the bottom line, isn’t it? Thank God for God. Thank God, as Psalm 23 does, that even when we walk through the valley of the shadow of death, he is there with us. Thank God, as Psalm 22 does, that he has not despised or disdained the suffering of the afflicted. Thank God, as Job teaches us, that we don’t have to bury our grief and anger, but can bring them to God honestly; for Job challenges God fiercely, but his challenge is rooted in his faith, and so at the end God says of him, “He is my servant, and he has spoken of me what is right.” Thank God for God, because that is the root and beginning of faith; to quote Wayne Brouwer again, “Only the grateful believe, and faith itself which seems to soar in times of prosperity needs the strength of thankfulness to carry it through the dark night of the soul.”

One man who well knew the truth of this was Martin Rinkard, a Lutheran who was the only pastor in Eilenberg, Germany in 1637. This was the time of the Thirty Years’ War, and in that year Eilenberg was attacked three different times. When the armies left, they were replaced by desperate refugees. Disease was common, food wasn’t, and Rinkard’s journal tells us that in 1637, he conducted over 4500 funerals, sometimes as many as 50 in a day. Death and chaos ruled, and each day seemed to bring some fresh disaster. But out of that terrible time, Martin Rinker wrote these words:

Now Thank We All Our GodNow thank we all our God

With heart and hands and voices,

Who wondrous things hath done,

In whom His world rejoices;

Who, from our mother’s arms,

Hath blessed us on our way

With countless gifts of love,

And still is ours today.O may this bounteous God

Through all our life be near us,

With ever joyful hearts

And blessed peace to cheer us;

And keep us in his grace,

And guide us when perplexed,

And free us from all ills

In this world and the next.All praise and thanks to God

The Father now be given,

The Son, and Him who reigns

With them in highest heaven,

The one eternal God,

Whom earth and heaven adore;

For thus it was, is now,

And shall be evermore.Words: Martin Rinkart; translated by Catherine Winkworth

Music: Johann Crüger

NUN DANKET, 6.7.6.7.6.6.6.6.

Thank God for God. Only the grateful believe.

Ministry as trinitarian work

I noted last month that I was looking forward to reading Dr. Andrew Purves’ book The Crucifixion of Ministry: Surrendering Our Ambitions to the Service of Christ, and had been ever since reading a version of the book’s introduction in Theology Matters. It’s not a long book, only 149 pages, but I read it slowly; it’s dense material, requiring thought and reflection and intentional engagement. I’m still processing it, and I expect I will be for a while.

At the moment, though, I’m only doing so indirectly. One of the blurbs on the back of Dr. Purves’ book is from Dr. Stephen Seamands, a professor at Asbury Theological Seminary; the blurb reminded me that his book Ministry in the Image of God: The Trinitarian Shape of Christian Service had been sitting on my shelf, and my to-read list, for quite some time. On my last trip, then, I made sure to toss it in my bag so I could start reading it once I finished Dr. Purves’ book. It proved to be a wonderful pairing.

The core of Dr. Purves’ argument is that ministry isn’t something we do, because our own ministries aren’t redemptive; only the ministry of Christ is redemptive. Thus he writes, “The first and central question in thinking about ministry is this: What is Jesus up to? That leads to the second question: How do we get ‘in’ on Jesus’ ministry, on what he’s up to? The issue is not: How does Jesus get ‘in’ on our ministries?” We need to understand the work of ministry in light of “the classical doctrines of the vicarious humanity (and ministry) of Christ and our participation in Christ through the bond of the Holy Spirit,” and understand that true ministry, redemptive ministry, happens not through our work but through Christ working in and through us. Thus Dr. Purves speaks of “the crucifixion of ministry,” the displacement and death of our own ministry in favor of the ministry of Jesus.

Where Dr. Seamands’ book is proving to be such a wonderful complement to this is in the fact that he makes the same point but sets it in a trinitarian context. He agrees that, as he puts it, “Ministry . . . is not so much asking Christ to join us in our ministry as we offer him to others; ministry is participating with Christ in his ongoing ministry as he offers himself to others through us. . . . The ministry we have entered is meant to be an extension of his. In fact, all authentic Christian ministry participates in Christ’s ongoing ministry. Ministry is essentially about our joining Christ in his ministry, not his joining us in ours.”

Where Dr. Purves focuses on unpacking that truth, however—and rightly so, since its implications for how we minister are significant—Dr. Seamands broadens the picture: “The ministry we have entered is the ministry of Jesus Christ, the Son, to the Father, through the Holy Spirit, for the sake of the church and the world.” As he notes, Jesus’ ministry on Earth was directed to and guided by the will of the Father, rather than being driven by the needs, desires, demands and complaints of the people around him. “Of course, Jesus often met human needs and requests, but . . . they did not dictate the direction of his ministry; his ministry to the Father did.” This is a profoundly freeing thought for those of us who too often find ourselves captives to the wills and whims of people in our congregations—which I suspect is most of us in pastoral ministry, at least some of the time.

In discussing the role of the Spirit, at least in the first chapter (I’m not that far along in the book as yet), Dr. Seamands focuses on the fact that “only through the Spirit can we discover what the Father is doing,” and thus keep the work we’re doing oriented to the Father rather than to the church and the world. This is certainly critically true, and he’s right to emphasize the importance of surrendering ourselves to the Spirit’s guidance and leading; but I think he underemphasizes the fact that it’s also only by the Spirit’s empowering that we can in fact “get ‘in’ on Jesus’ ministry,” because it’s the Spirit who unites us with Christ and fills us with the power of God. Without the Spirit filling us by connecting us with God who is the source of all life, we have no power to do anything beyond our own skills and hard work; and as Dr. Seamands notes, “ministry . . . demands more than our best, more than anything we have to offer. To participate in the ongoing ministry of Jesus, to do what the Father is doing, we must be filled with the Holy Spirit.”

Between these two books, I suspect I’m going to be spending a lot of time thinking about these things, and their implications for the work to which God has called me within his church. I would invite you to do the same.